The Stress Test of Federalism

States’ Rights, Federal Authority, and a February Session Built for Conflict

Editor’s Note: This series is not about cheering state resistance or defending federal centralization. It is about understanding how one of the oldest unresolved issues of our country’s founding — states’ rights versus federal authority — is manifesting in the modern day, and which mechanisms will shape the conflict.

—

When lawmakers created the short session more than a decade ago, the intent was narrow and pragmatic: to make technical budget adjustments, clean up unresolved issues, and pass low-hanging fruit, while largely deferring most major policy decisions to the next long session.

Over time, short sessions have increasingly become a place to introduce legislation establishing negotiating positions, signal governing priorities for the election underway, and plant flags for the next long session.

In other words, February sessions have become less about bills that pass but about where the political fault lines are drawn.

Oregon’s February sessions were not designed to resolve big issues, let alone sort out historically relevant questions about the intersection of states’ rights with federalism and the exercise of centralized power.

Why 2026 Is Different

The defining characteristic of this session is anticipation, but not like the way we anticipate the state fair coming at the end of summer — more like how the Louisianans anticipate the next Category 5 hurricane.

Recent news reporting and political chatter has fueled speculation about whether Oregon could be among the next states to face a Minneapolis-style federal surge involving one or more federal enforcement entities.

Rather than waiting to see whether those dynamics materialize, lawmakers appear to be preparing in advance. Across both chambers, a flurry of legislation has been introduced by individual legislators, but the whole may be more than the sum of its parts.

The shift this year is not simply about what bills are being introduced, but how they are designed to work together.

Detractors say many of the proposals introduced this session carry an undeniable symbolic dimension, but symbolism alone does not explain their design. As a practical matter, what is emerging appears to be a legal framework to assert brighter lines of state authority.

The House and the Senate: Two Roles, One Strategy

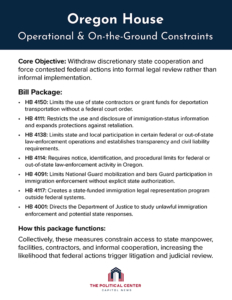

In the House, the emphasis has been on how federal authority operates physically within Oregon’s borders. Legislation has focused on immigration enforcement, law-enforcement cooperation, and National Guard participation, narrowing the circumstances under which state resources or personnel may be used in support of federal action.

The cumulative effect is not the nullification of federal law, but the deliberate withdrawal of state-enabled implementation ease. Federal authority remains intact, but its exercise becomes slower, more visible, and more legally contestable.

The Oregon Senate is more focused on the systems that make enforcement and federal pressure possible in the first place, such as the flow of information, data usage, election administration, public lands, health care oversight, and long-term financial exposure.

By asserting authority at these upstream points, the Senate raises the cost of federal intervention long before enforcement reaches the ground.

A Deliberate, Redundant Design

Looking at individual bills introduced this year tells only a part of the story. As a package, they build redundancies into layers of assertions of state authority.

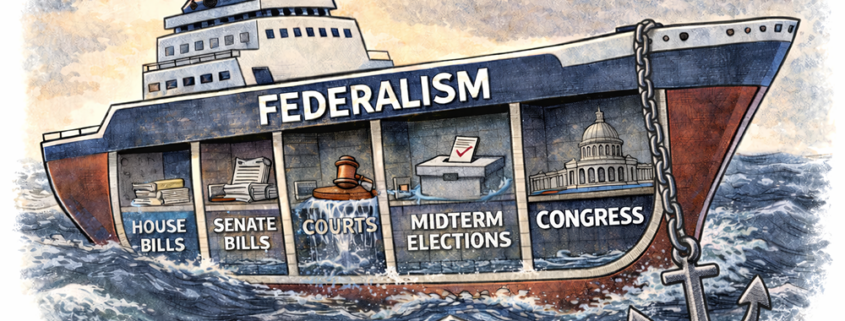

What is being built here is a structure engineered to survive damage, like the way ships are built with compartments and the expectation that some sections need to be able to fail without sinking the whole vessel.

Instead of relying on a single statute, a single legal theory, or a single point of resistance, authority is intentionally spread across multiple policy domains and enforcement mechanisms.

This is a legal strategy engineered to operate under stress — one that anticipates pressure, mixed rulings, and the likelihood that not every provision will survive intact. If one provision “takes on water” through litigation, delay, or invalidation, the surrounding structure is designed to remain intact and operational. It’s how engineers design a submarine to absorb incredible pressure by spreading it throughout the structural components of the ship.

But at what point does survivability replace governance as the goal?

A Very Old Argument, Newly Surfaced

It’s easy to view the current moment through the lens of personalities: President Donald Trump versus Oregon Attorney General Dan Rayfield; federal authority versus state leadership; one administration pushing and another resisting. That framing is tempting, but it misses the deeper point.

What the country is grappling with now is not a personality conflict so much as a recurring structural one. The debate over how much power should reside in a centralized federal government, and how much should remain with the states, is among the oldest unresolved questions of the American experiment. The reason that history matters here is not nostalgia, but design.

From the country’s founding, the Republic has wrestled with this question. That tension was embodied early on by figures like Alexander Hamilton, who argued that national strength required centralized power, and Thomas Jefferson, who believed liberty was safest when authority stayed close to the people and the states.

These disagreements were not abstract. They shaped the first political parties, divided early administrations, and fueled personal animosities that could turn vicious. The most famous example — Hamilton’s fatal duel with Aaron Burr — was not fought over a single policy dispute, but over clashing visions of power, governance, and the future of the Republic.

The founders understood that this conflict was not resolved, and they designed a system meant to absorb it rather than eliminate it.

James Madison captured that logic succinctly in Federalist No. 51, writing that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” The point was not to eliminate conflict, but to design institutions capable of managing it so the system could outlast even its most volatile personalities.

When read in that light, today’s disputes are less about who holds office and more about whether the system still functions as intended when personalities collide.

Where the Real Decisions Will Be Made

In theory, Congress authorizes, federal agencies regulate, and states implement. In practice, modern federalism increasingly resolves elsewhere: in the courts.

And while the Supremacy Clause does mean the federal government will likely prevail in at least some of these disputes, the timing of that resolution eventually matters. The frameworks being built this session do not appear focused to preventing or avoiding conflict, but rather to surviving it by governing though injunction.

Litigation can serve as pause points that stretch for months or even years. The practical objective may not be permanent victory, but rather slowing action long enough for the current administration to leave office.

Whether you align more closely with Alexander Hamilton or Thomas Jefferson, the mechanisms being built this session merit close attention because it is not a single act of resistance or cooperation, but a governing posture designed for uncertainty. One that anticipates friction, relies on litigation as a pause point, and treats time itself as a strategic tool.

This session is unlikely to resolve the tension between state authority and federal power. But it makes clear that the conflict is no longer episodic or theoretical. It is structural, anticipatory, and increasingly engineered into the machinery of government, and that reality more than any individual bill will shape what comes next.